A visit to see George Lailey’s lathe at MERL

On Monday 22nd September I visited the Museum of English Rural Life in Reading once more in order to try and find answers regarding the design of the pole lathe and its paraphernalia. This blog post is very much aimed at other pole lathe turners, but non turners may find it interesting to understand the many steps that have to go towards recovering information about a craft that died out in a country and why it is ideal to keep supporting them before that happens, because it becomes a whole load more difficult after!

In this free-to-visit museum is the pole lathe of ‘the last bowl turner’ in England, a fellow named George Lailey. It can also be possible to arrange with the curators to go behind the scenes in the archives and see his tools, mandrels and some examples of his work. I fully recommend visiting the museum, but I hope that this article means that only the keenest of turners will need to trouble the curators for the full behind the scenes experience. The lathe is on public display, but we were only able to interact with it under supervision. Please don’t touch without asking if you do visit! All photos are copyright ‘Museum of English Rural Life, University of Reading’.

I was lucky to be joined by Ali Asadi, another talented pole lathe turner who had not visited before. Ali’s interactions with the objects reminded me of the first time I went (two years ago), wide-eyed and full of enthusiasm and reverence for seeing George’s lathe and tools. When I visited before I saw the backrest and assumed George had it because he was an old man…how wrong I was. Ali has also turned a lot of large and beautiful nests, and so it was lovely to see how moved he was to handle the large bowls in their archive which George had turned by foot power alone. There was also a 19” platter, which was quite spectacular.

However for me, this trip was less about looking a treen and more about looking at some specific aspects of his lathes and tools, armed with questions that I hoped I would get answers too. George died at the age of 89 years and was turning until the end. It gives me great hope that it is possible to turn on the pole lathe without the pain currently affecting my whole body. His lathe is subtly different to those used these days and I have started to understand why (for example the backrest).

I wanted to look in detail all parts of his turning experience: His tools, mandrels (and cores), methods of manufacture, lathe construction and lathe dimensions (and also to estimate George’s height) so I can adjust mine for ergonomics using his as a reference.

George’s Height

Firstly George’s height. I am 6’4” so the lathe looks tiny by comparison. By viewing photos of him behind the lathe in MERL, and comparing the height of Ali by the lathe, this time compared to where the centres should be (around nipple height or just above), I am confident George was 5’4”-5’5”. I’ll now compare the lathe measurements from the Lailey lathe to those on my current lathe and see if there is a correlation with our height, fingers crossed!

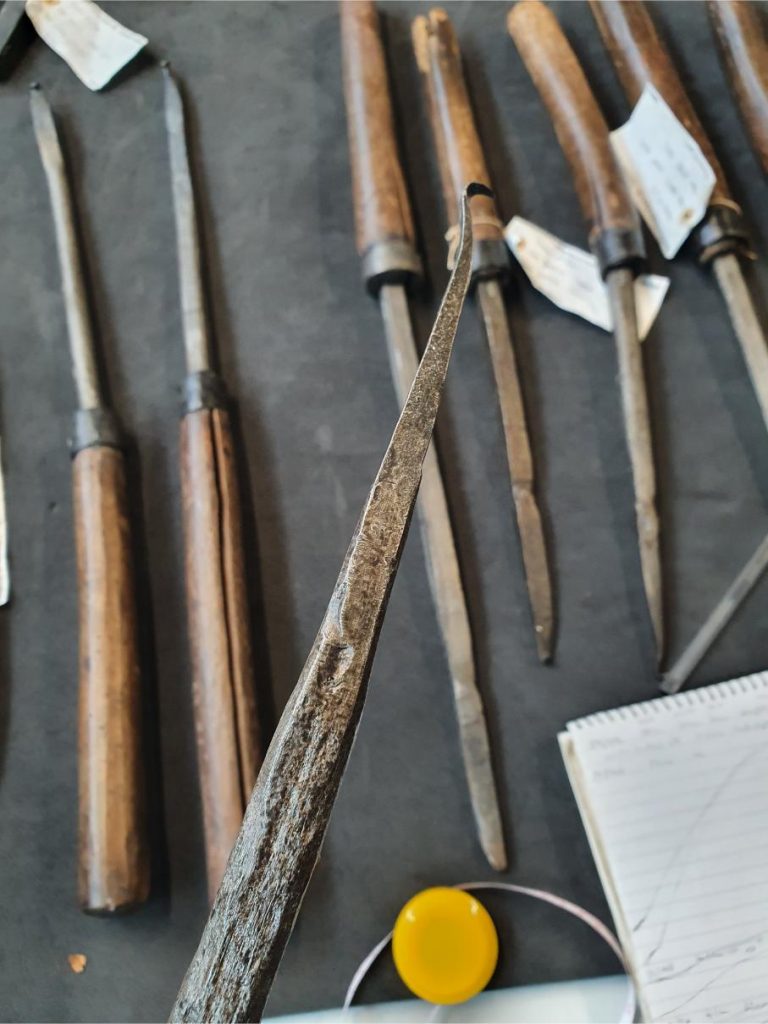

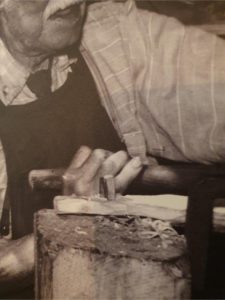

Tools

I was delighted that a few handles existed on some of the hook tools (Nb. these were known as irons). I took some measurements and have a few more working theories to try out on my lathe now. A lot of George’s handles were much shorter than ours so they could be braced at all times against the body without twisting the spine. Knowing the length of the tool and George’s height will allow me in time to estimate where he stood and where his backrest would have been (it is in the wrong position in the museum), and by extension where my backrest should be. In turn I hope this will let me know how this needs to be varied for different heights of turners so I can teach people on a lathe set up specifically for them.

The nesting hooks in general were very small ‘tip up’ tools, but the hook generally only curves round 90-110 degrees. It never went the full 180 degree bends of a regular tool. (I also took an A3 sheet and traced all the curves, get in touch if you think that’s be useful to you and I can share a copy)

Handle lengths were all around 30cm and often with a gentle curve downwards towards the toolrest.

A lot of the tools had tool steel welded onto wrought iron shafts. Some looked like they may just be made of wrought iron though (it was hard to see the weld).

Mandrels & Cores

As I hoped to find, the mandrel spikes were all roughly in line, but slightly offset to prevent a catch from knocking the mandrel loose (if all spikes are exactly in line) (Nb. these were known as mampers). I think this is the main mistake with how I currently make my mandrels. Before I make any firm conclusions though, I want to read the chapter on cores found at Coppergate in more depth to see if their spike mandrels were similar. Plus of course experiment with the ones I currently use. Spikes were all knocked in with the grain not across the grain.

Methods of Manufacture

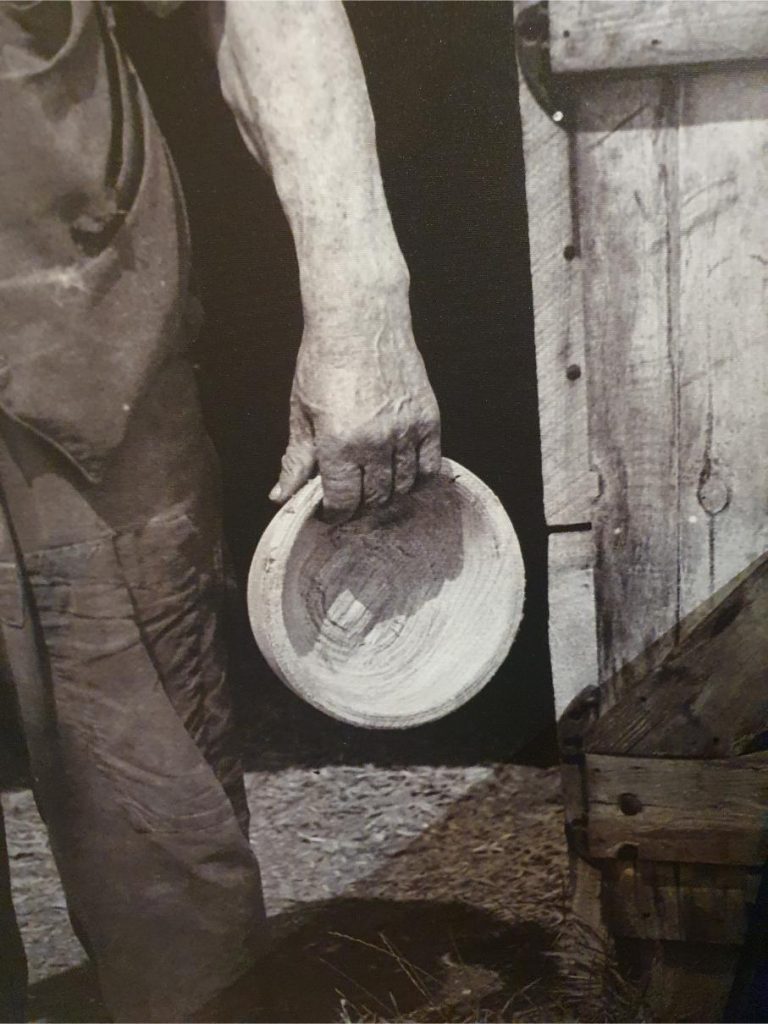

I was not actually expecting to find evidence for these things, but I was glad to. Firstly, there is a photo of George holding a bowl and the core has clearly been separated with a wedge. I am already aware of this technique for nesting in France, Germany and Ireland, so it makes sense that George also did it. Secondly some of the smaller cores had growth rings that suggested they were the remnant from the bottom of the bowl not the top of the bowl. It suggests that part of the process of making nested bowls is to remount each bowl once split off with a wedge. I have seen other articles supporting the practice of twice turning bowls, but it is something I need to try before saying more on the matter. Needless to say I am quite excited by this as it explains a lot of things about bowls I’ve seen in museums going back some time. There were also some cores which have clearly been split with the wedge. Unfortunately no evidence of the wedges used still exist.

Lathe Construction

I am indebted to MERL for letting me handle the lathe and indeed make some adjustments as some of the lathe had become assembled wrongly over the years.

Firstly I had a good look at the tailstock poppet and the wedge(s) in particular (Nb. George called them puppets not poppets). Of note here were pieces of leather to put inbetween, which Ali and I summised were to increase grip (another thing to test). It is worth noting the fit of the wedges in the poppet and indeed the poppet in the bed was very loose before it was hammered home! This may mean that not much precision was required here as we have been aiming for (which pleased me greatly). The bed itself has a small gap of only 2” which is made possible by the tri-angulated pedal holding the cord in place. I suppose this has the advantage of a more stable bed, and also that it catches most of the shavings so they can be shoved off in front of the lathe so the pedal can continue to run free. The wedge was hammered in to secure the wedge from the front of the lathe bed. This was corroborated by the photo of George behind the lathe and examining the wedge. Up until now I have tried this both ways, but it is always good to know what worked for George (as it was probably best in the long run!). Ali theorised that the lower part of the wedge on the poppet was there because this poppet was used on the other lathe in the workshop and then moved here when the original fell apart. I have seen photos of a different poppet being used on the lathe before that.

The pedal has ended up put together wrongly according to photos I found and with the museum’s permission I updated it so it was the right way round (George must’ve been turning in his grave 😉 !). Where he pressed his foot there are some old rags (to improve comfort?), and I was delighted that when handling the pedal I discovered the three holes in the pedal that appear on all other lathes of this era across the continent. These holes allowed the user to move the position of the drivecord, to prevent the mandrel fouling, when the workpiece is turned around. It is remarkable how every turner across the continent had this and other similar features that we have mostly ignored these days.

I was sad to find that the backrest was in totally the wrong position and I couldn’t see how it was attached to the lathe to see if it was adjustable. Many of these old lathes had adjustable backrests, and I was keen to see if George’s was similar, but it was therefore not possible to find firm evidence for this. Ah well, can’t win ’em all!

The toolrest support did not look like it was the original, but there were photos showing a similar construction. There were only around 3 nails in it to hold the toolrest which suggested a limited variety of things being made due to the limited positions it would be in. I was excited to find that the toolrest (whilst looking extremely rustic) had been axed to be almost exactly the profile of an axe handle at the point it is held. This was exceedingly comfortable to hold, and something I will definitely experiment with. The metal spike in the poppet that the toolrest looped over was a very loose fit, but the old photos all show a missing wooden peg wedged in to hold it tight. Another improvement I’ll suggest and potentially make next time I visit MERL!

(copyright: “Museum of English Rural Life, University of Reading” P DX323 PH1_L16_21.jpg))

Finally, it is nothing to do with ergonomics, but the bit I got most excited about was listening to a 6 minute excerpt from a BBC interview with George. In it he refers to his first bowl he turned and I am 100% convinced this is the bowl sat atop his lathe even now and held in by a number of nails! A rite of passage for turners perhaps, as I have seen these bowls on other old lathes too!

In time I hope to share more information on dimensions and so on, but I need to cross reference it against my lathe and test theories out before making any firm conclusions. It would be great if others joined on this journey to understand ergonomics though, so if you are feeling pain during turning, think if any of these changes could help you and have a go!

In summary, I found a lot of answers to my questions, but also discovered a few more too. It is really exciting to see the similarities in how bowls were nested and the lathes and tools used across the whole continent. I have a lot of testing to do back at the workshop, but the dots are joining and each day I feel better equipped to understand how the pole lathe turners worked back then. I’ll have to wait until December though, as my back is against the wall making until then!

I am exceedingly grateful to MERL for letting me in behind the scenes. I fully recommend visiting their brilliant museum first as a day visitor though, as the whole place is bursting full of great exhibits of interest to the green woodworker!

Interesting with the back rest. I remember old time pole lather (like me now !), always had a back rest when spindle turning.

For sure Peter, if you look back all the old photos so many had backrests. One of my winter jobs is to make my spindle lathe. excited to devise a fixed pedal for it too.

Hi Geoff,

This is fascinating and so important, I wonder if there isn’t an opportunity to collaborate with someone like Zed Shah to document your journey. As a more visual learner it would be wonderful to follow your progress on film.

Thanks for your time and effort;I hope your back appreciates it.

Oh and the look on Ali’s face made my day😃

Bon courage

Hi Mike, thanks glad you appreciated it. For sure, would be great to do a video with Zed at some point. Perhaps once I’ve written the book I intend to is write as a means of promoting it. All the best,

Geoff

Thanks for sharing your findings Geoff, I will be following with great interest as you experiment back at the workshop with your new found knowledge. I have no doubts your enthusiasm for the subject will benefit many turners for years to come.

Cheers Jon! I hope so too!