Pricing a 6″ Wooden Bowl

This blog could quickly descend into a multi-page essay, so to keep things clear I’ll try and focus solely on how to price a simple 6″ wooden bowl. This blog is aimed primarily at makers who are trying to price their work, but also may be of interest to customers trying to understand my (and other makers) prices. Having said that, it is still a long read and it definitely skips some parts I’d love to spend more time on.

Before we begin, here is a quote of what pricing feels like to many of us (lifted from the comments section of an instagram post I did recently): “(Pricing seems to be) a mixture of careful calculation, finger in the air, black magic and desperation.”

I hope this blogpost reduces some of the magic element, but I can’t guarantee on the desperation 😉 ! Also, before you read further, please be aware I’ve never read a business or economics book. What you read is based on six years of thought, observation and opinion building. You’re bound to disagree with me somewhere and I’m still learning! I am just about to do a Cockpit Arts Centre Business Course, so I suspect I’ll be updating this blog come February!

I think pricing stuff is actually remarkably easy. Just price it and a customer will emerge. What I suspect makers want insight into is how to price objects so they sell and maximise profit. Well, my thoughts on this are that your price has an impact on this, but more important is the quality of your work and your ability/luck in finding customers, so perhaps that should be the focus of this blog (but isn’t).

To begin with I want to define four terms I’ll use a lot: Cost, value, price and market rate.

– Cost – the costs to the maker in creating the object for sale. These are many and varied, some easy to define, some less so.

– Value – how much you or a customer thinks your object is worth. How we value something also depends on many things.

– Price – in a way this is the easy one. The price is the price you exchange an object for.

– Market rate – the average price of your object across all makers (For a handmade 6” wooden bowl in the UK, my view on this is about £35 currently (Sept 2025)).

In summary, my opinion is that there are three rules to pricing:

– the price is ideally the same or higher than the market rate.

– the price should exceed your costs.

– the price should be equal to or exceed whatever someone (including yourself) values your piece as being worth.

The market rate rule:

Firstly a bit of history on my pricing ‘strategy’. I started trying to sell my bowls for £5 each at Tyntesfield House with the Somerset Bodgers. I sold very few, as I believe customers felt that I didn’t value myself or my work. When I made them £10, I started selling, but I got the impression that the customers felt like they were getting a ‘steal’ (which they were). That feeling didn’t sit well with me, so I made the price £20. People kept buying (at a rate which my levels of production couldn’t keep up with). So I made them £30, this was the market rate at the time, which my peers were selling an equivalent bowl for. I felt a bit of a fraud doing this as I was still (relatively) inexperienced, however the customers still kept coming, albeit at a rate that allowed my production levels to never be over-stretched.

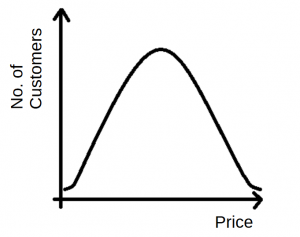

The final thing to add is if I make the price above the market value, people still buy them (albeit from a reduced pool of customers). I have tried this to an extent with bowls I deem to be really special. I view this relationship as a kind of normal distribution (it isn’t, but it helps my brain), like shown below, where the peak corresponds roughly the market rate. So, my advice, if you want an easy way to price your work, is to do your research on similar makers, and price it similar to the market rate.

Personally, I struggle with producing volume on the pole lathe, so if I want to make a living I need to make fewer items sold at higher prices. Thus, I have a smaller pool of potential customers, so I have to do a lot more work to find enough customers, but once I’ve found them or they’ve found me, I believe this can work out well too. I’m just starting to put that effort in.

The Costs rule:

If you calculate your costs, you will probably find it is below the market rate (we hope so anyway). This creates a margin. I artificially aim to introduce a margin of 10%, this is your profit. Without pricing so you make a profit, it is tricky to survive as a business, as it is harder to invest in your business and skills, plus if sales dry up, there is nothing in reserve to last until they pick up again. As an example remember a lot of makers bank on making their sales at Christmas, now imagine that last Christmas (2024), it rained on three out of the four possible selling weekends, thus massively reducing customer numbers and also sales. Without a margin this sort of event can scupper a small business.

Costs will be different for different makers, hobbyists for example may choose to not charge as much for their time. For me, I split my costs into three: the making costs, the time costs and the selling costs. See table below for a 6” wooden bowl turned on the pole lathe. Perhaps one day I’ll do a blogpost with a more detailed breakdown of each of these categories, but the reality is that I can’t do that for every single item I make, as it’d take way too long and is dependent on yearly volumes etc.

| Making costs | £6 |

| Time costs | £20 |

| Selling costs (via online shop) | £5 |

| 10% profit | £3 |

| Total | £34 |

The total gives a price of £34. Thankfully this makes our bowl pretty much equivalent to the market rate of £35! If I was slower at turning, my price would exceed the market rate and I would have to either accept a lower wage/hour, put my prices up (no bad thing), or consider making a different object which I could achieve at an equivalent or better price to the market rate.

I got another comment on Instagram, saying that “(Pricing) has always felt a bit of a dark art to me, based on a mixture of time spent, materials and gut feeling of what seems about right.” There was then a reply to that saying “Ah, but as you improve, your time diminishes”.

This is an interesting point, and for a while had me thinking that the old adage “time is money” didn’t hold true. Then another maker explained to me that actually it takes time to build your brand, and that ‘extra’ money you now get from making quicker and selling easier to a larger audience, is actually paying for all your years of training and standing on market stalls to get to that point (seven years and counting for me… still don’t feel like I’m there!).

So does ‘time is money’ hold true? These days they are related for sure, but I feel the impact of time on the price is way too complicated to be considered as a sole way to price our work. The making time is such a small percentage of time spent on creating a wooden bowl. As such I tend to not use this costs method to calculate the final price, other than to get a rough calculation to make sure I’m not at risk of making a huge loss.

The Value rule:

In response to my Instagram post someone responded: “The basic truth is something is worth what someone is willing to pay. There are so many factors to take into consideration. It takes time and experience to learn.” I agree with this statement, but I try to phrase part of it slightly differently.

Rather than it being ‘what someone is willing to pay’ (I used to say this too), I now prefer to think of it as ‘what someone (including myself) values my piece as being worth.’ I feel like ‘willing to pay’ (if read by a customer (although I understand the intent of it)) is a little too crude, and makes it seem a little like the maker has the opportunity to take advantage of the customer. Having said that I don’t feel guilty over charging a high price for something if I value it as being worth that. I am also always looking for ways to increase the value of my work, so as to be able to make a more comfortable living from my work.

So how do I value my work? Well mainly (like many things) through trial and error and making mistakes. Once you’ve lived the experience of making something you’re super proud of and then selling it for a price that leaves you a little deflated, you know to value yourself higher. i.e. what I ask myself is, ‘what price would I be happy if someone paid for this?’.

The big follow-up questions my head then turns to are:

– ‘how do customers value things’ (for example, thinking about competitors like ceramic bowls, etc)

– ‘how can I add value to my work?’ (think about how my work is presented etc)

– ‘can I sell to high-end customers, yet also make my work accessible for other customers?’

These are all massive topics though, worthy of their own blogpost one day!

Summary

In my opinion, the price is often not the thing that sells a bowl, its qualities are, e.g. its finish, uniqueness, the story behind it and how it is presented. In other words, selling my items seems to be less about how I price it and more about how good I am at making and then finding the right customer match. So I try and go easy on myself with price, set it where I’d be happy according to those three rules, and then go find some customers!

I am comfortable with my method, but I appreciate it may not work for everyone. Setting prices is a personal thing. If you see things differently I’d love to hear from you in the comments or privately if you’d prefer.

If you want to look at my bowls and see if those prices reflect how you would value it, then please have a look here. If you, perchance, wanted to buy a bowl to support these blogs, that’d be much appreciated too 🙂 ! And, as usual, please leave feedback, comments, and future blog suggestions below!

Interesting read, as a hobbyist something I struggle with only just started selling the odd thing, I just want to be able to take a few classes and maybe attend a few more events, if i charged per hour it would be way too high Im not a quick carver, im getting faster but alot if faffing at the end thanks for sharing this

Hi Paul,

Glad you found it interesting! I was in the same situation once too. I remember it being hard to believe that someone could want to buy my items, but over time I gained confidence and put my prices up to the market rate (even though i too was still too slow to call that making a living). Speed of making has come over time with experience. Good luck on your journey with this 🙂

All the best,

Geoff